There's a portfolio I still have, pictures of custom cabinets and furniture made when I was a cabinetmaker. Some of it published in shelter magazines or books on design. A reference in the "Biennial Design Book, 1979". Detritus.

There's an apartment on Park Avenue, which became famous, for a time in the 70's, because it was the residence Richard Nixon wanted to move into after his presidency. "Wanted to" is the operative phrase here as the building's co-op board was so afraid of the security arrangements a former president would require, and the possible attendant disruption to their lives, that they voted not to allow him to buy the residence. This was reported in various newspapers of the day and raised a little controversy, which soon died down. But the apartment, itself, became somewhat notorious, so when it was sold the price was high, maybe 3 million dollars, which, at the time, was a lot of money.

It was approximately a 4500 square foot floorplan, and about 1500 square feet - the "public" living and dining rooms - had a white marble floor of 24" x 24" x 1" thick tiles. In addition, the entry floor was a marvelous, intricate mosaic of black and white marble. It would cost a fortune to get something like that made now. It probably cost a fortune when it was done, however many years ago.

The owners hired a designer, S., to "do" their new home, while they lived, for the duration of the construction work, at the Carlyle Hotel (nice temporary digs!). S. often used a contracting company I worked for (I was the shop foreman) so I was invited, along with perhaps 10 different subcontractors of various trades, to "walk" the apartment with her.

That's how S. designed. She didn't use blueprints. She would march through an apartment, point at the ceiling, announce "6 high-hats here", or wave at a wall, "knock that down". If a better picture of what she wanted was needed, she would have one of her two assistants draw a full-size illustration on the wall. Cabinets, for instance, were done this way. Then the responsible trade would provide working drawings based on her ideas, she'd edit or approve, and that's how the plans would be created.

At this point you could hear about 10 pencil points snapping as the subs did shocked double-takes. Ed flinched, but imperceptibly. He was a cool guy.

"S.", he replied, remaining calm, "are you sure? This floor is priceless. And getting it out of here would require jackhammers. And I have a funny feeling that the people in this building, this particular building, might be more than annoyed at the amount of noise that jackhammers make. I don't think we can do it."

Lounging against a wall was Ernie, our truckdriver. He was a friendly giant, 6' 5" tall, maybe 300 pounds, sometimes used for demolition projects, sometimes to just lift things. An unskilled but dependable guy.

Ed called to him. "Ernie, get a sledgehammer and a cold chisel, let's see what we've got." Ernie returned, tools in hand, and was pointed to one marble tile, in the corner. "Take it out.", Ed directed.

And Ernie started slamming. Marble, when attacked like that, rings, a high-pitched, bell-like sound that echoed through the apartment. Working hard, on his knees, ripping the sledgehammer through the air, Ernie finally demolished one piece. It took a while. Ernie was sweating. Ed could see this wasn't going to work. But he had an idea.

"S., you don't care how we do this, you just want a wood floor, right? So we'll cover the marble. We'll remove all the base molding, make a substructure out of firring strips that we'll glue down, go over that with underlayment, lay the oak floor, then reinstall the base molding. How does that sound?"

"That's fine, Ed", S replied, waving a bejeweled hand as she left. "You're so ingenious. That's why I use you."

And the new oak floor was, indeed, beautiful.

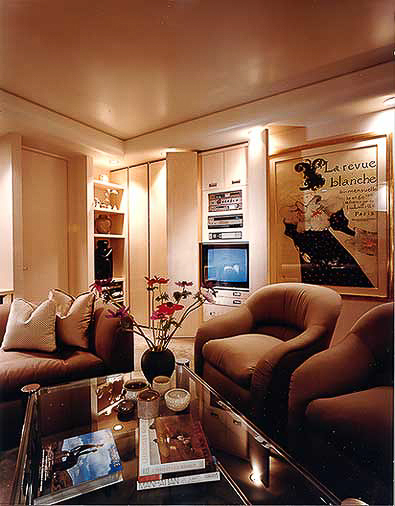

About two months later I returned to take portfolio pictures of the library. I entered, and was shocked to see that the apartment looked exactly as we had left it. Empty.

No one had moved in.

I began the photography when a real estate broker arrived, prospective buyer in tow. From him I learned that the original buyer had decided that he didn't want the apartment, after all. A townhouse around the corner was more to his wife's liking, so he bought that, moved in there, and was in the process of selling this apartment. The broker was showing it. And, as he was leaving I heard him proclaim "...and underneath this oak floor is the most amazing marble...".

I'm told removing the oak floor was a bigger job than installing it.